Kubernetes — in depth

Kubernetes, hereinafter referred to as k8s, is an open-source system for automating deployment, scaling and management of containerized applications. Due to it being a recent technology (released less than five years ago under the Apache License 2.0), this section attempts to summarize both its terminology and its overall orchestration mechanisms.

Containers — A new era of deployment

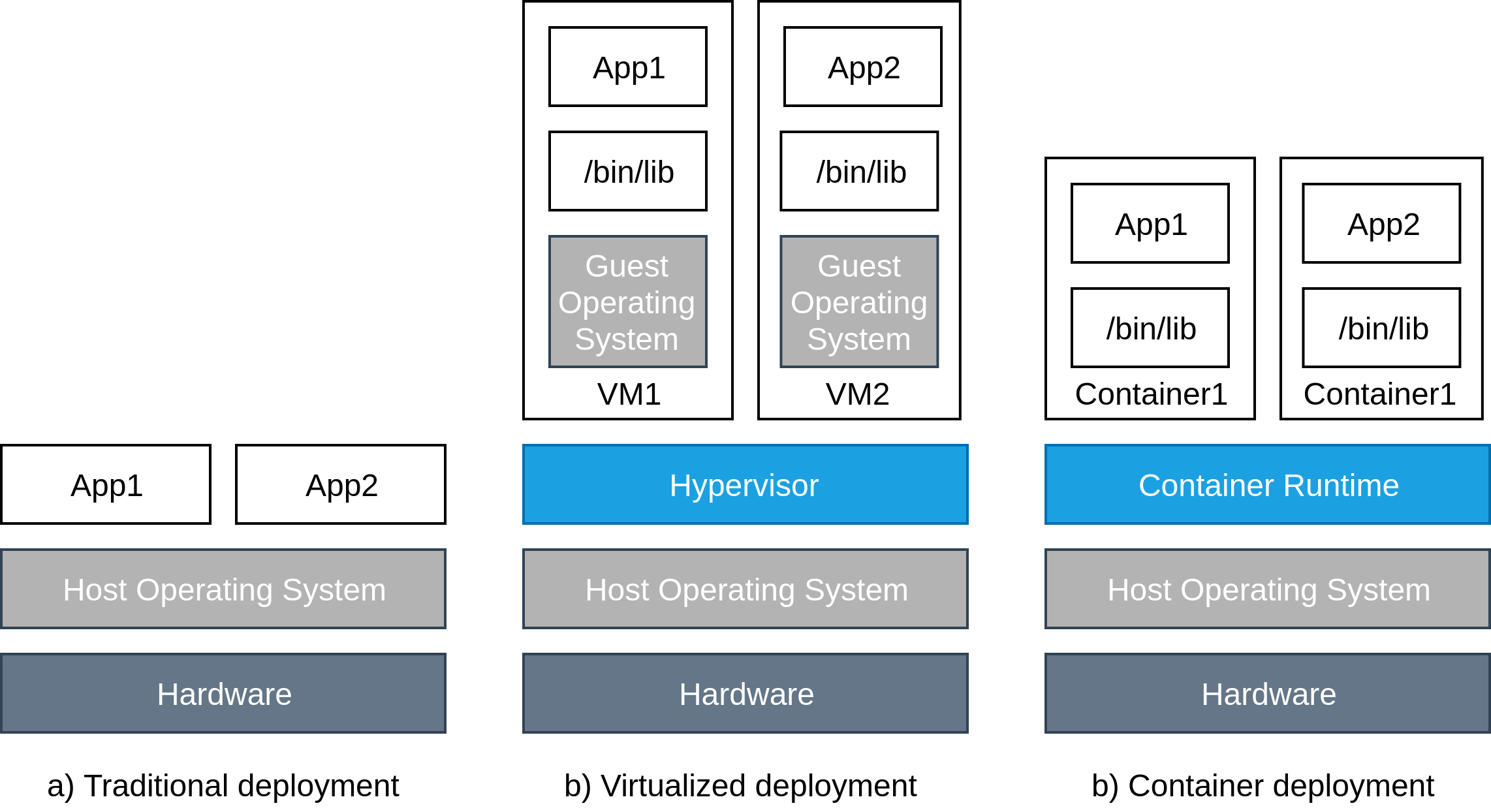

The massive adoption of k8s marks the entry into a new era of deployment. Initially, deployments were applied directly onto physical servers. However, the traditional deployment era suffered from performance issues stemming from the inability to define resource boundaries between different applications. The introduction of virtualization tackles this issue by allowing multiple Virtual Machines (VM) to run on a single physical server. These VMs provide a level of security through isolation of scalable component as well as reduce the strain on hardware. Nonetheless, each VM is a full machine running its own operating system on top of the virtualized hardware.

Docker Containers — Infrastructure base building block

At the forefront of this technology is Docker, a platform for developers and sysadmins to develop, deploy, and run applications with containers; a container being a standard unit of software that packages up code and all its dependencies so the application runs quickly and reliably from one computing environment to another.

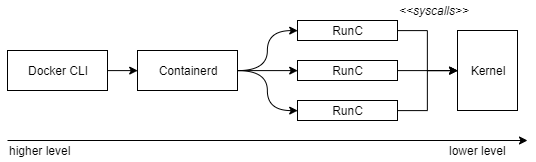

In order to instantiate a container, an executable package that includes everything needed for the application (runtime, libraries, code, configuration files) also known as an image is required. For example, a client can ask the docker daemon to pull an Ubuntu image from a registry (public or private) which can then be instantiated as containers in the host machine. Nowadays, the docker daemon is broken up into three main components:

- runC is the lowest level runtime component used to interact with the OCI (Open Container Initiative) interface. This module interacts directly with the kernel in order to create namespaces, cgroups, capabilities, and filesystem access controls. In practice, a container is an environment running in an isolated set of kernel namespaces.

- These container lifecycles are then managed by the containerd daemon which also takes care of setting up the networking and image transfer.

- Finally, the Docker engine only provides high level CLI for users and downloading images from docker registries.

High Level Architecture

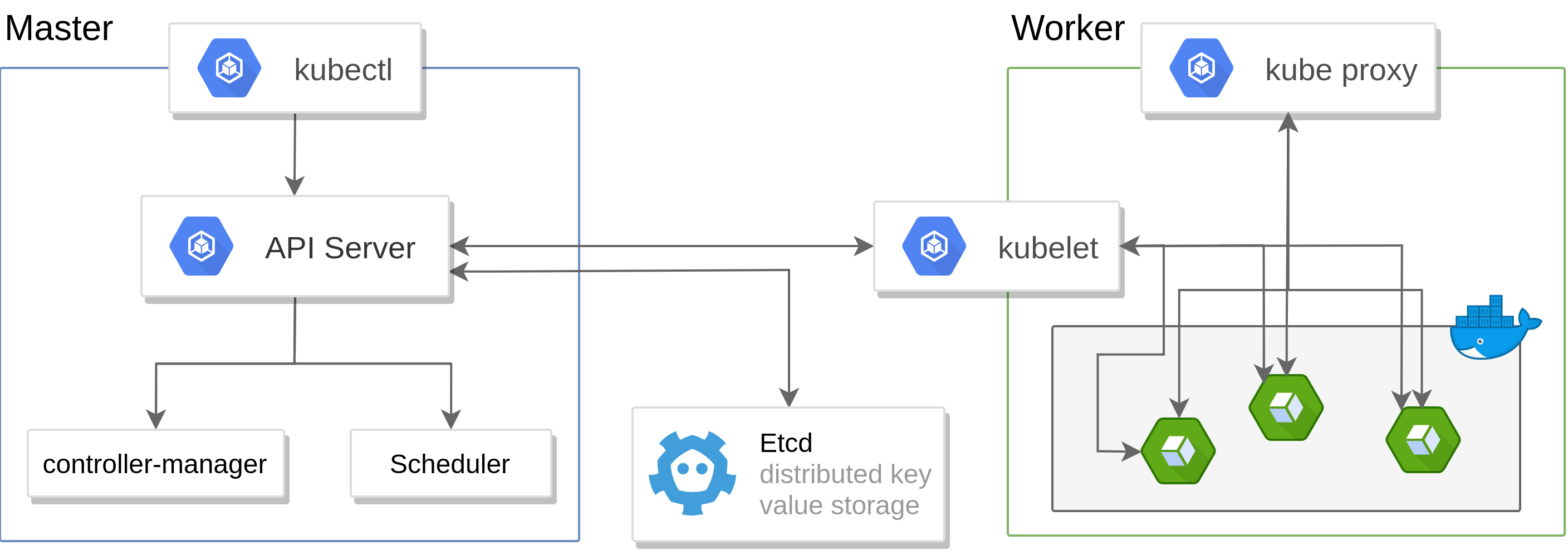

K8s uses these previous building blocks in order to create an orchestration tool for managing microservices or containainerized applications across a distributed cluster of nodes. These node follow by default a client-server architecture in which there is a master node acting as the entrypoint for all administrative task and control point for all worker nodes in the cluster. Is it important to node that this separation is not exclusive as a master node can also be a worker node.

Master Node Architecture

The sole entry point for the system in this setup is through an API server hosted by the master node. This server processes REST requests, validates them, and executes the bound business logic. For instance, a request to list all pods in the API whose name is v1 is ‘GET /api/v1/pods’.

This node also hosts some etcd storage which are distributed key-value stores storing shared configurations and service discovery which can be queried via REST. The previous example would in reality be routed to the etcd storage because it stores information regarding pods, jobs and their scheduling, etc…

As in any distributed system, resources in k8s clusters are scarce and require a scheduler which decides where to deploy a component thanks to information gathered regarding available resources on worker nodes. An extra level of control can also be achieved by the controller-manager which watches the shared state of the cluster and makes decisions and changes in order to reach the desired state.

Worker Node Architecture

Worker/Slave nodes are where pods are run, so Docker is used to provision and start containers here. Since these nodes depends on scheduling by the master node, this communication is guaranteed by kubelet which gets the configuration of a pod from the apiserver and ensures that the described containers are up and running and fetches information from the master etcd. Finally the kube-proxy service deals with individual host sub-netting and expose services to the external world.

Base security mechanisms

RBAC and the Kubernetes API

The Kubernetes API represents a fundamental fabric of Kubernetes through which all REST API calls, including object declarations are handled. As such, managing access to this component is primordial in order to maintain a secure Kubernetes cluster. Two categories of API users is distinguishable: human users and service accounts (used by pods within the cluster). Both of which has to go through three phases in order to gain access to the cluster (Authentication, Authorization, Admission Control).

In order to access the cluster (either through kubectl, client libraries or REST request), an user has to authenticate using at least one of the allowed methods. First of all, the k8s-api serves on port 443 with a TLS certificate which is required by the user in order to suceed the handshake.

-

Authentication - Contrary to other concepts in k8s, users are neither referenced nor stored by the API as an object. Thus, the authentication technically boils down to an HTTP request which is analysed by its auth modules (client certificates, token, etc.) in order to garantee that the requests comes from a specific user. For serviceaccounts, this is done through a service account token which can be mounted on the path

/var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccountto allow automatic authentication. -

Authorisation - Once the first step is complete, the aforementioned request must be authorised by one of the following methods: Node authorization (internal authorization that allows for kubelet to query the API), ABAC (authorization based on request attributes) and RBAC (authorization based on roles)

The role based access control (RBAC) is one of the most granular method of authorization and can be leveraged to allow for pods within the cluster to communicate with the API. Defining this method of access regulation requires:

- Role: An assignment of a list of interactions (verbs) that can be applied to an array of resources in specific apiGroups. This can be restricted to a namespace or applied cluster wide (Cluster Role). For instance, the following yaml declares a role that allows for getting and listing deployments (that are in the apps/v1 API namespace):

rules:

- apiGroups: ["apps/v1"]

resources: ["deployments"]

verbs: ["get", "list"]

- Service Account and a RoleBinding: the separation of the role, the rolebinding and the service account allows for fine grained access control to the API and easy revocation. Using the RBAC properly therefore allows for programmatically managing the cluster within the cluster itself in a completely secure manner.

Pod Security Policy

Fine-grained access control is also implemented on the pod and container level through Pod security policies. This is done through defining a series of conditions which the affected pod must present in order to be accepted to the system. Policy enforcement is therefore done directly at the admission controller (before the creation of the resource) and independently of the container at hand. These policies can be summarized in the following overlying themes:

-

Privilege and Escalation: policy inherited from the underlying docker component which would grant a container all capabilities that the host possesses and lifts all the limitations enforced by the device cgroup controller (see Appendix lib-container)). As a rule of thumb, no container that requires leverage over the host network stack should be privileged.

Privilege escalation is by default banned through preventing the setuid binaries from changing the effective UID within the container. This feature is however prone to vulnerabilities as seen in the CVE-2019-5736 through which exploits of the runC library could be used to obtain root execution from a docker container.

-

Volume and filesystem: allows managing access to certain kubernetes volume types, enforcement of file system group as well as restricting access permissions on different paths.

Appendix

Libcontainer namespaces and cgroups

Kernel namespaces are fundamental in containers as they allow isolation of:

- Process trees (PID namespace) : processes in different namespaces can have the same PID. Thus allowing multiple process trees can coexist in the same system and facilitating container migration (as PIDs within the container are maintained).

- Mounts (MNT namespace) : isolates a set of mount points for a process or processes in a given namespace, providing the opportunity for different processes on a system to have different views of the host’s filesystem.

- Networks (Net namespace) : provide a new network stack (along with a loopback interface, network interfaces, routing tables and iptable rules) for each process within the namespace.

- Users/UIDs (User namespace) : isolates security-related identifiers and attributes, in particular, user IDs and group IDs, the root directory, keys, and capabilities

- Hostnames (UTS namespace) : isolates hostnames and domain names.

These namespaces are vital in sectioning off different containers within the same OS. Kernel control grous (cgroups) on the other hand, allow accounting and limiting resources used by processes.