Kubernetes — basics

Kubernetes objects are abstractions that represent the state of the system. These persistent entities describe what containerized applications are running, the resources allocated and available as well as their behaviors (restart policies, fault-tolerance). Unlike normal infrastructure declaration, these objects portray the desired state of the cluster which k8s will try to satisfy. This “record of intent” is declared in a declarative fashion in yaml and interpreted by kubectl, k8s’s default CLI.

Pods — Base execution unit

A Pod is k8s’s basic execution unit, a process running on the Cluster similar to a container in a monolithic deployment. Unlike its counterpart, a Pod declares an unit of deployment and thus can be used in two ways:

- Single container pods which encapsulate the container serving as an adapter for k8s to better manage said container (with resources needs, volumeMounts etc…)

- Composite container pods which wraps multiple containers that are tightly coupled and need access to a shared resource. This approach although less common in practice allows for the implementation of design patterns which help solve and reuse common problems with distributed architectures.

One of the most important concept related to pods is that they follow an ephemeral lifecycle, they are not meant to survive if a failure of any kind were to occur (scheduling failure, node failure, lack of resource, etc…) and do not self heal in order to reach the desired state. Therefore, Pods are rarely individually created but provisioned by high level abstractions called Controller. A pod’s lifecycle can be summarized as follows:

- Scheduling: A controller requires the creation of a pod to satisfy its desired state and communicates it to the k8s API. A pod with the corresponding specs is then scheduled for creation.

- Lifespan: If the resources demanded can be satisfied in a node, it is assigned an unique ID (UID) and will remain bound to that node until termination or deletion.

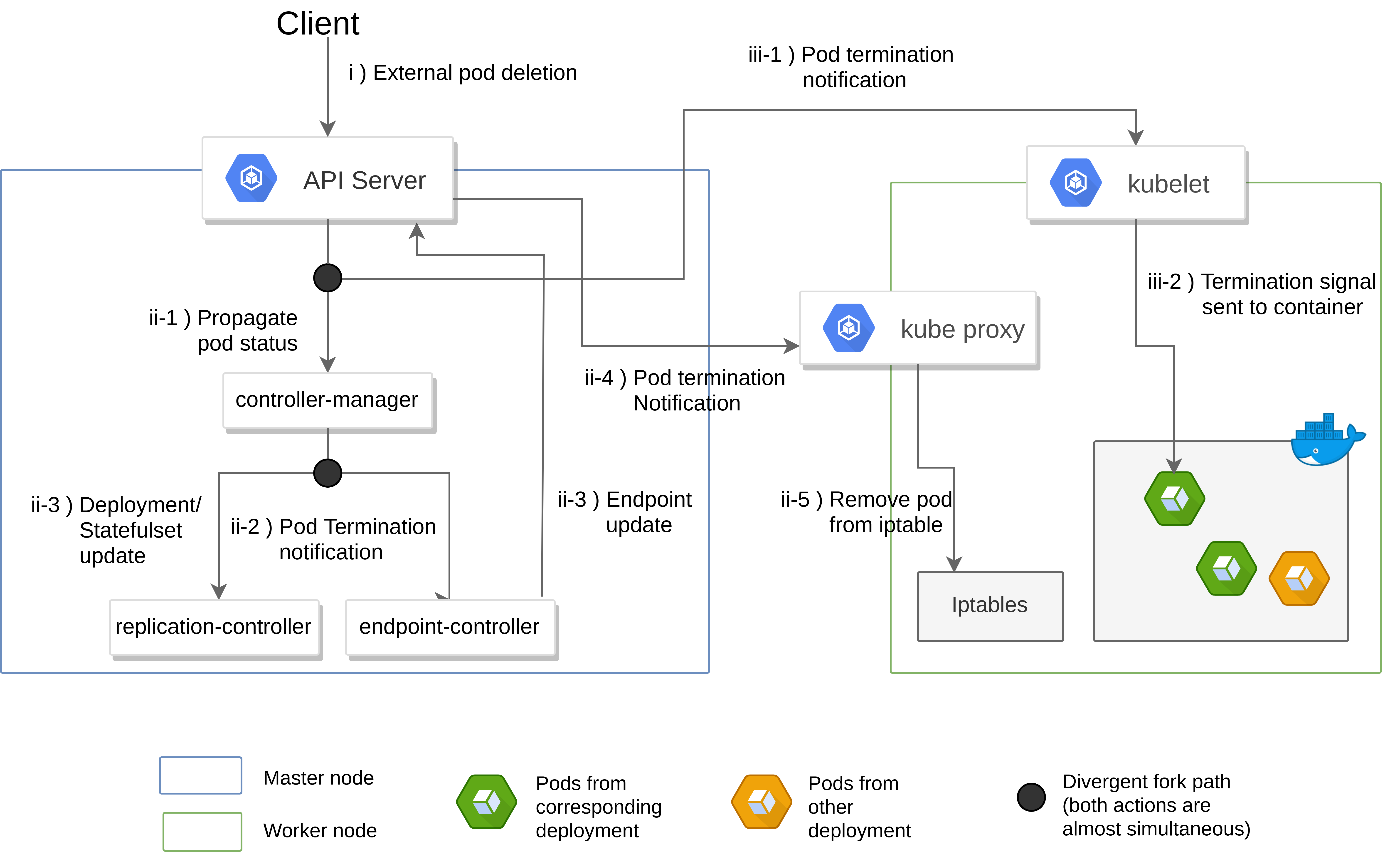

- Termination: If the restart policy is set to “Always”, the pod would be restarted (maintaining the same UID) no matter the exit code of the encapsulated containers. A restart policy set at “OnFailure” would do the same thing but only with non error exit codes. Finally, a “Never” restart would lead to the termination of the pod. Non persistent associated volumes would then be unmounted, allocated resources freed, kube-proxy iptables update and bound endpoints removed.

Services — Base networking unit

As most components in k8s are not durable, keeping track of which IP to connect to in order to link up components over the network is impossible, thus making an abstraction like Services mandatory. Services in k8s define a logical set of Pods determined by a selector to connect to rather than a fixed set of IPs which allow for dynamic internal routing for deployments that do not care which instance handles the routed request. In practice, service selectors are used to match with labels meaning that only objects having said labels can communicate using the aforementioned service. Services can then be put into three main categories.

-

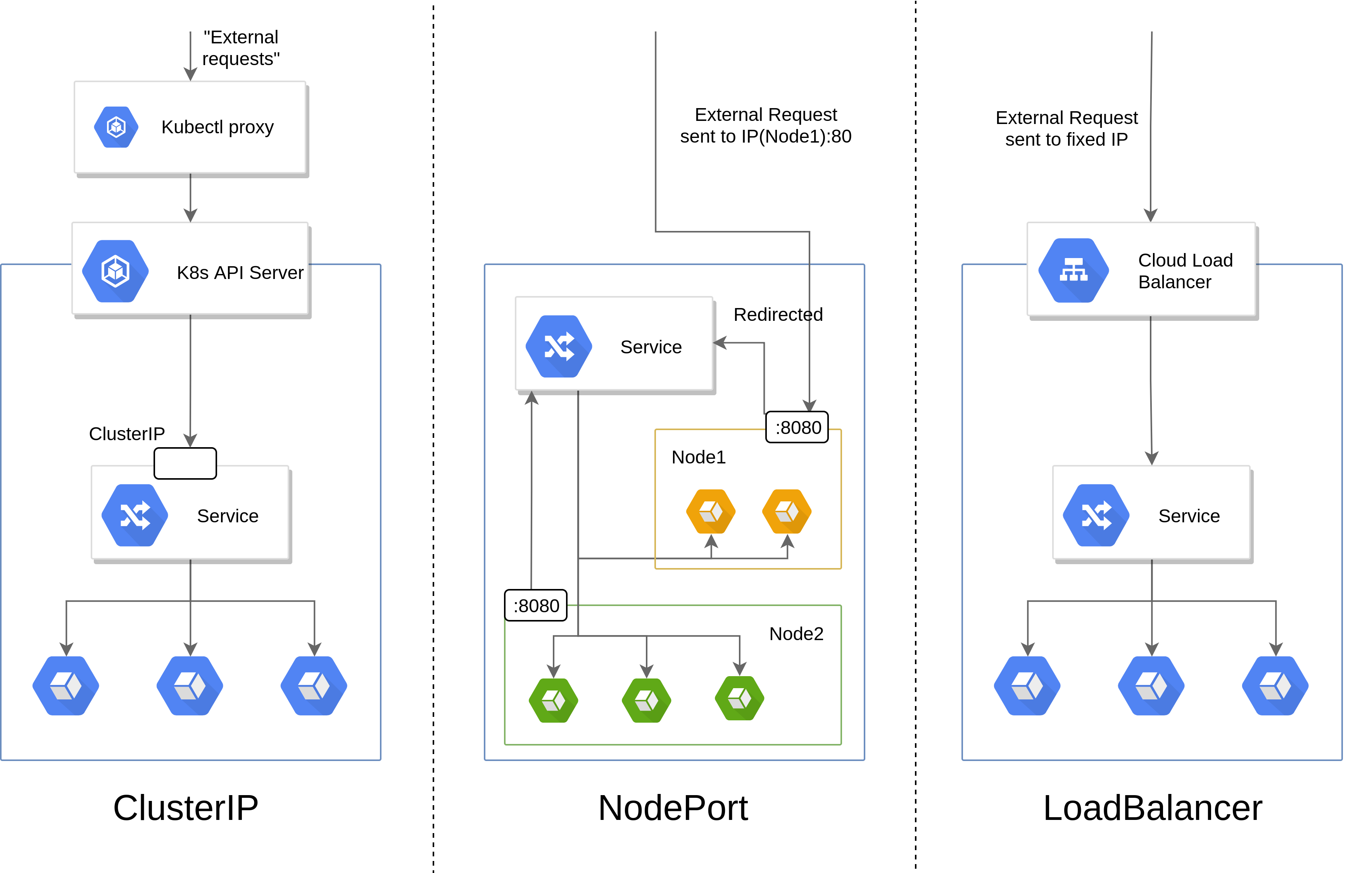

ClusterIP : the default service type in k8s ensuring that a given set of destination ports on a set of machines that match the selector are reachable only from within the cluster. For example, if a ClusterIP service with the name nginx-service in the default namespace is defined and targeting an nginx deployment, all pods within that namespace can communicate with the nginx pods through the domain name nginx-service.default.svc.cluster.local at the ports declared.

-

NodePort : exposes the service to external traffic by opening specific ports on all nodes. Requesting \textit{NodeIP:NodePort} would be permitted from outside the cluster, introducing a major security concern.

-

LoadBalancer : exposes a service to the Internet assigned to a fixed external IP to the Service (the creation of the external IP often being relegated to the cloud provider).

-

ExternalName : maps a service to a CNAME record (e.g. foo.bar.com). Extremely useful for mapping external services such as a database with a floating IP outside of the cluster.

Ingresses — External access API

Ingresses provide a mean for services in a cluster to be accessible from the exterior either through HTTP or HTTPS. It can be configured to give Services externally-reachable URLs, load balance traffic, terminate SSL / TLS, and offer name based virtual hosting but requires an Ingress Controller to fulfill its task.

In usual deployment scenarios, a LoadBalancer is used to expose the Ingress Controller deployment which then manages and routes requests according to the ingresses defined.

Volumes — Base storage unit

The ephemeral nature of containers also has its impact on storage. A k8s volume’s lifecycle strictly follows that of the Pod that encloses it. Therefore, a volume bound to a pod outlives any containers allowing for data to be preserved across container restarts.

In order to avoid confusion going onwards, the following terms will be used:

- A volume is bound to a pod once its declared in the .spec.volumes field

- That volume could then be mounted to any numbers of containers within that pod simultaneously once its declared in the .spec.containers.volumeMounts

Kubernetes supports a myriad of volume types that differ in their storage implementation and their initial contents.

Persistent Volume Claim

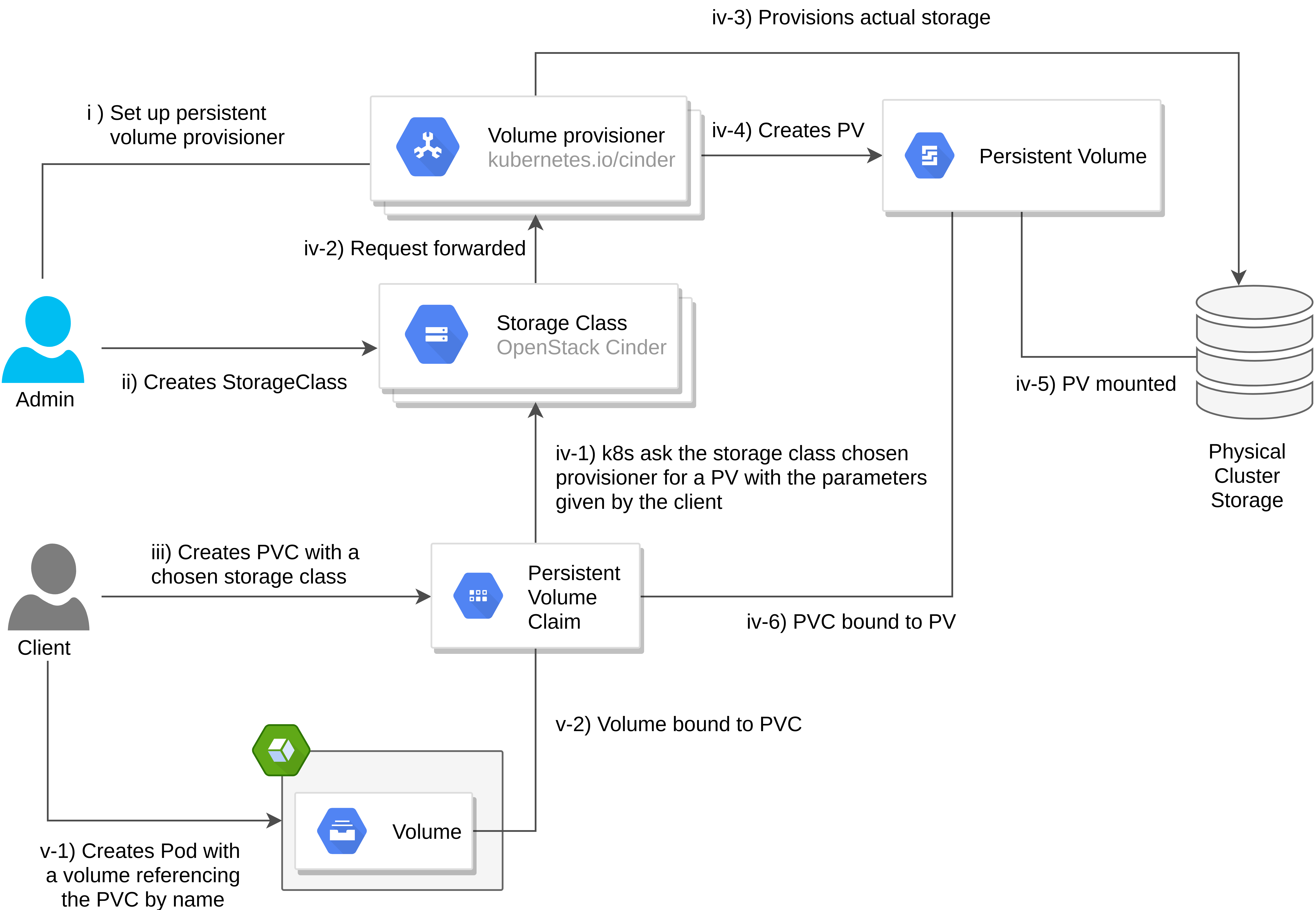

Persistent Volume Claims (PVC) is the most common volume type, providing an abstraction as to how storage is provisioned and consumed independently of the cloud environment.

In order to provision a PVC, an actor states a claim to durable storage backed by a Persistent Volume (PV). Note that, a PV’s lifecycle is managed by k8s independently of any object that mounts it, thus, making it non ephemeral. Furthermore, a storage class can be defined to enrich the volume’s feature such as volume expansion and reclaim policies. Therefore, an object can consume storage resources in an agnostic manner, having no prior knowledge of the storage class nor the private volume satisfying the claim goes into detail how Openstack provisions PVs).

HostPath

A HostPath volume mounts a file or directory from the host node’s filesystem into the given pod. This volume type permits applications to access to Docker internals through /var/lib/docker or to interface with the kernel through /sys and thus, mandatory for native k8s monitoring.

Controllers

As previously stated, Pods were not designed to be created individually but by controllers; high level abstractions that ensure the desired state of the cluster matches the observed state.

Deployments

Arguably the most commonly used controller, the Deployment controller encapsulates Replicasets and Pods in the k8s’s resource hierarchy. The Replicaset object being k8s’s main mechanism to managing scaling of pods (ReplicationController being deprecated) which is used to maintain a stable set of replica Pods adhering to a given Pod template manifest, running at any given time.

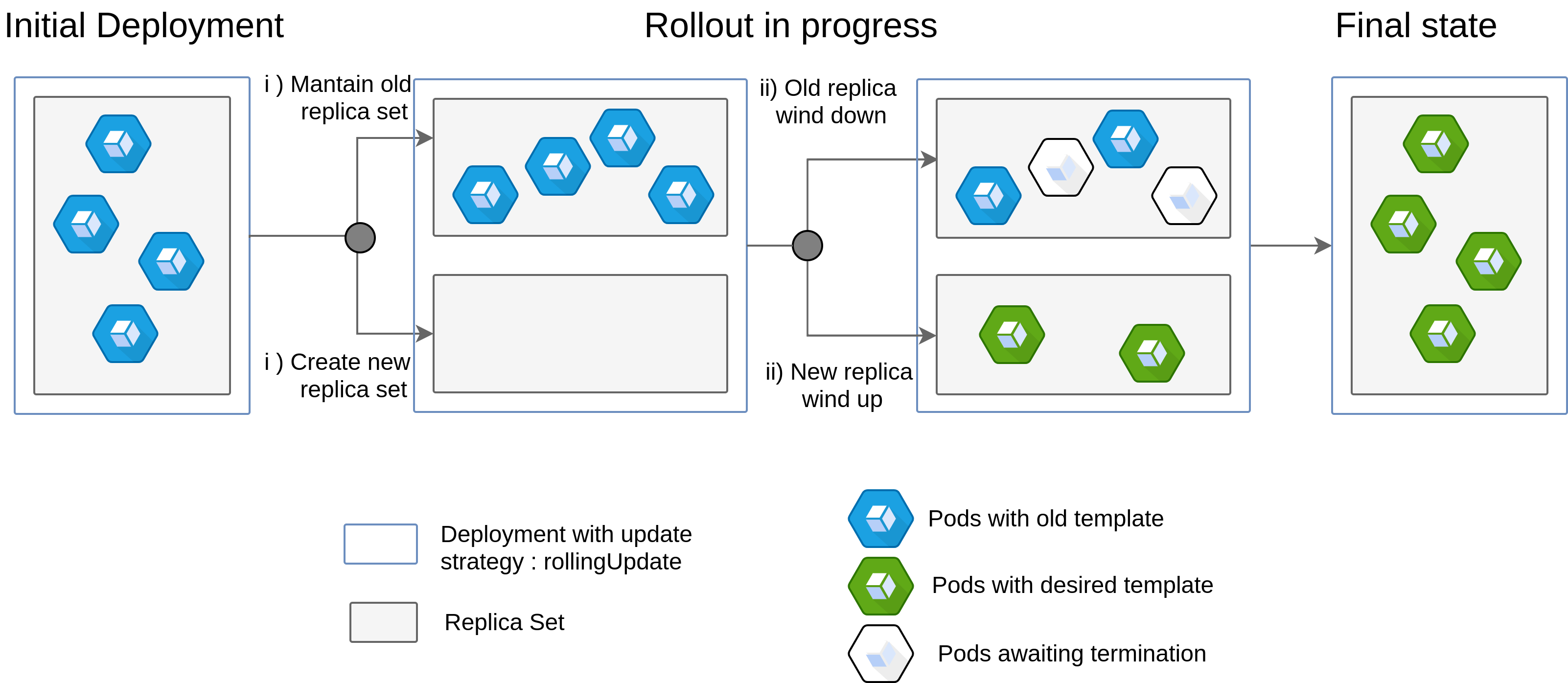

Since this API object is meant to be a low level object, Deployments are built upon ReplicaSets to offer a wider range of usages. One of those usage being rollout and rollbacks which help solve problems with updating and reverting Pod templates whilst maintaining all the service provided by the cluster. A Rolling Update, the default update strategy for k8s deployments represent in practice a blue-green deployment technique.

Statefulsets

A Statefulset is quite close to a Deployment but adds a sticky identity for each of their Pods. This persistent identity allow for stable (persistent across pod scheduling) and ordered deployment and scaling.

For instance, in a statefulset comprising of N replicas, each pod will be created sequentially in order from 0..N-1 and assigned an unique ID in that same range. As the goal of statefulset is overall order, termination of a Pod is only available once all its successors are terminated and scaling up require that all predecessors are Running and Ready. However since it does not create ReplicaSets, rolling back a Statefulset to a previous version is impossible.

Daemonsets

The least commonly used controller are Daemonsets which ensure that a copy of a Pod is run on a certain set of nodes. Its main usage case are node monitoring daemons (Prometheus for instance), logs collection daemons or cluster distributed storage daemon such as ceph.

Helm — Configuration management for k8s

Managing k8s’s complex environment and deployment can be done either through Helm, Kustomize or natively and therefore a technical choice has to be made for the vulnerability-assessment-tool’s case.

Kustomize

Kustomize is a k8s native configuration management not based on templating but rather on raw, hard-coded, static YAML declarations. These declarations when added together in a kustomization.yaml allow for development, staging and production environments to coexist. With features such as secret generator and config generator, this tool can update secrets and configmap and keep them separate from the static object statements.

If the k8s deployment were to be changed and published to the public repository, an user would have to: git pull from the latest branch, resolve conflicts if they made any changes to the files, apply the kustomize CLI to apply the changes.

Helm

Helm is a package manager for k8s which helps define, install, and upgrade even the most complex k8s application. Unlike Kustomize, Helm uses the concept of Charts, a set of templated yaml declarations with a “variable” file named values.yaml to provide repeatable update and rollbacks through each new release of the latter.

Although developing a chart is quite complex (due to the complexity of the Golang templating engine used), if published, it can facilitate k8s deployment for users of the open-sourced tool. On the consummer’s side, fetching an update to the Chart from version $a$ to version $b$ translates to running a single command: helm upgrade CHART_NAME