Eclipse/steady — Security and delivery considerations

Securing a deployment in a k8s environment cannot be restricted solely to k8s and has to extend to multiple context; starting from the application itself, to the container wrapping it, to the pod abstraction said container, to the communication between said pod and even up to the orchestration software configuration behind it.

Application tightening

Applying static and dynamic code analysis tool before releases is a mandatory stage in securing the application. A static code analysis tool examines the software code (as source code, intermediate code, or executable) without executing it with specific inputs.

For static analysis, Spotbugs is used in order to find bug patterns in the Java code base. Possible bugs found are categorized in a couple of categories:

BAD_PRACTICEandSTYLE: Violations of recommended and essential coding practice and anomalous coding styles. These issues do not affect security but should be addressed nonetheless in order to maintain the code base’s ease of contribution.CORRECTNESS: Apparent coding mistake resulting in code that was probably not what the developer intended. This category must be examined case by case in order to determine the mitigation required.MALICIOUS_CODEandSECURITY: Code vulnerable to attacks and addressing these possible vulnerabilities should be of the highest priority.PERFORMANCEandMT_CORRECTNESS: Inefficient code or flawed implementation of threads, locks and volatiles.

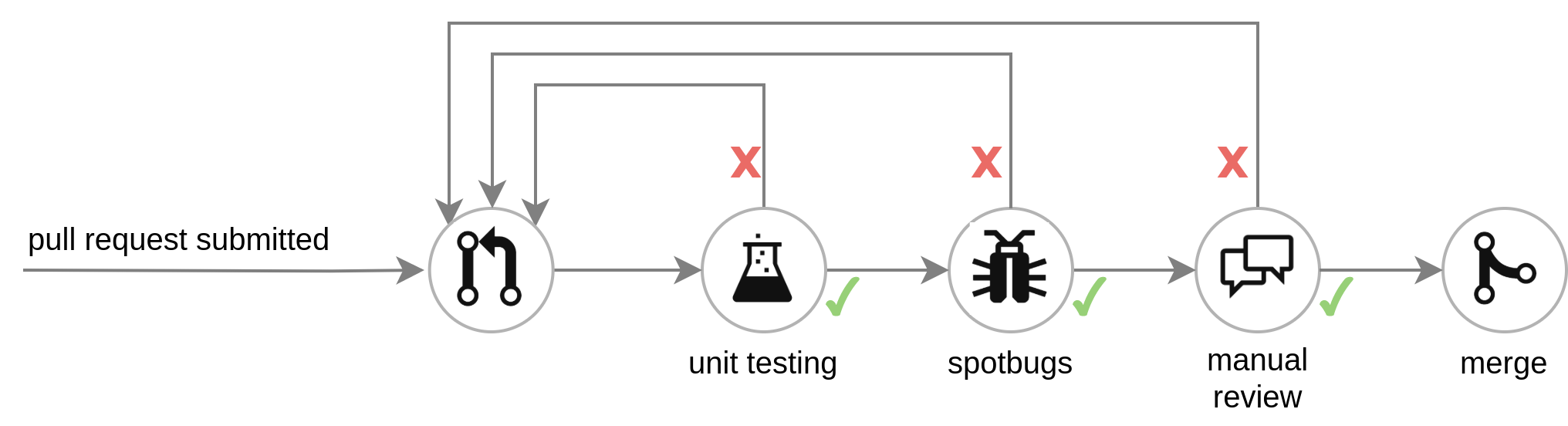

In order to properly enforce the mitigation of issues found by Spotbugs, a step is added to the pre-existing Travis pipeline that runs the Spotbugs goal and fails if any bugs in the MALICIOUS_CODE, SECURITY, MT_CORRECTNESS categories are discovered.

Container securing and delivery

In both production and development environments, the applications are containerized and a couple of major security considerations are to be put into effect.

Reducing the Docker image surface

It is recommended to use minimal base images such as alpine based images over debian based ones. Alpine images are smaller in footprint than traditional GNU/Linux distributions (requiring no more than 8MB for a minimal installation) and offers thinned out and split binary packages which gives better control over the environment installed. This reduction in size and the amount of general system libraries come with a reduction in possible exploit of vulnerabilities in said libraries. At the same time all binaries are compiled as Position Independant Executables (ensuring that the body of machine code function properly no matter its absolute address in the primary memory) with stack smash protection (which in turn limits possible damage afflicted by buffer overflow attacks).

Least privileged users

Docker containers that do not specify its USER defaults to executing the container using the root user. When that namespace is then mapped to the root user in the running container, it means that the container potentially has root access on the Docker host which put the host machine at risk of privilege escalation attacks.

Jib — A dual purpose solution

Jib is an open-source software published by Google that that builds optimized Docker for Java applications based on distroless containers.

Distroless containers, unlike Alpine or other small footprint base images have fundamentally different philosophies and approaches to building containers: whereas the former attempts to trim down a distribution to the limit at which it is sufficient for the app to run, distroless attempts to build the container from the standpoint of what the application needs. From this thought process, the distroless images are bootstrapped by selectively extracting debs (Debian package). For compatibility, apk was not chosen, thus substituting musl (alpine’s C standard library of OS’s based on the Linux kernel) with glibc (GNU Project’s implementation of the C standard library). Distroless containers therefore only contain the application and its runtime dependencies, without any package managers or shells (reducing even further the surface of potential attacks at the cost of harder debugging).

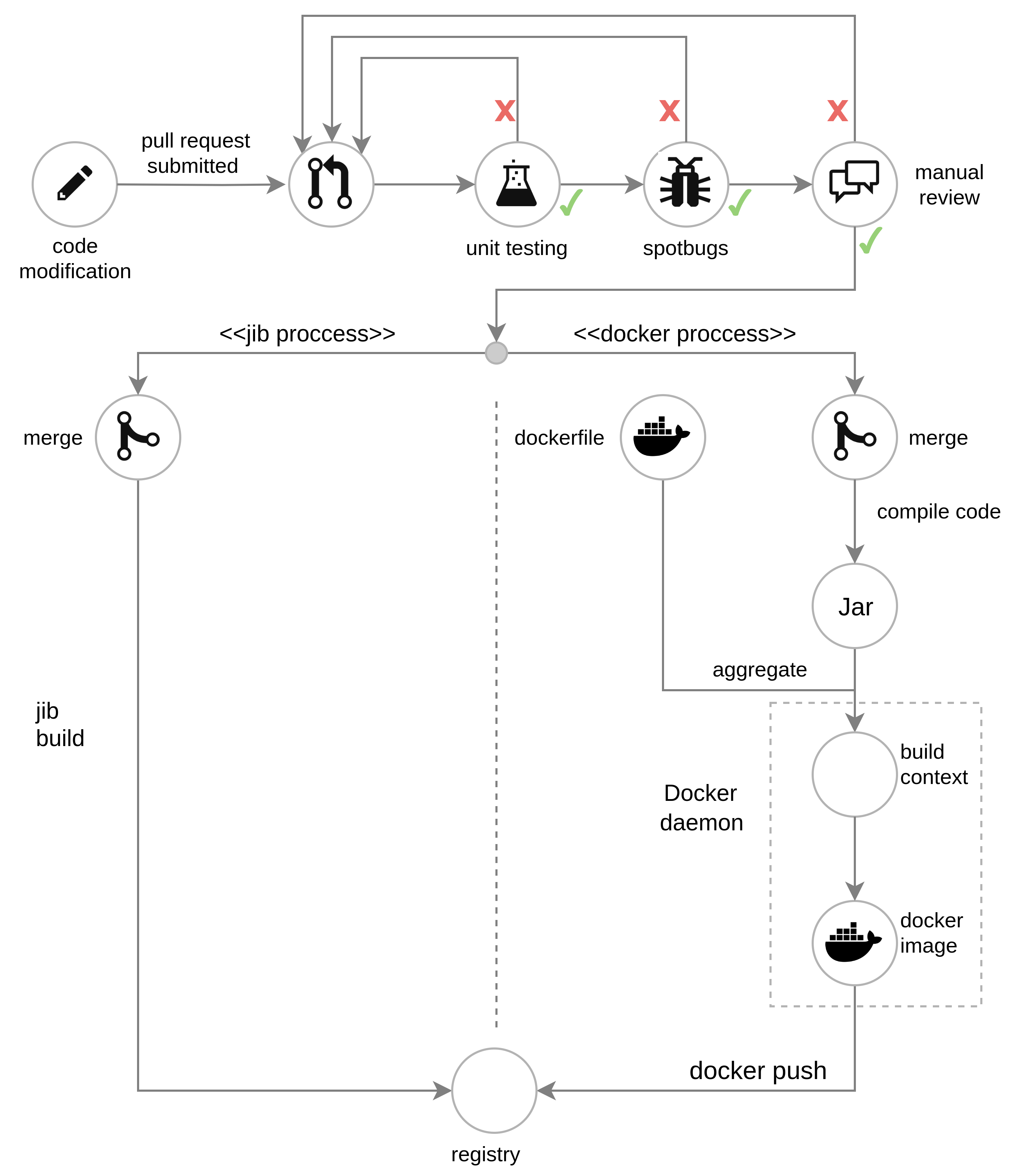

Jib builds itself on the foundations of the distroless base image to build Java applications. Unlike traditional build systems in which a Java application is built as a single image layer with the application JAR, Jib separates the Java application into multiple layers for more granular incremental builds. This increases the speed of image builds drastically, by only changing the layers that have changed to the registry. It also abstracts the packaging process itself as it runs as part of the Maven build without requiring a Dockerfile or a running Docker daemon.

Thee simplification of the deployment process along with the added benefits of a secure container makes it a viable replacement to using docker images in our use case.

Performance wise, the exploded tar springboot containers built by jib also create observable speedups when it comes to startup time on all spring version to its fat jar counterpart (see Spring benchmark). This performance gain comes at the cost of slightly bigger footprint than alpine based images of around 20-30MB in average.

Skaffold — Continuous delivery for Kubernetes

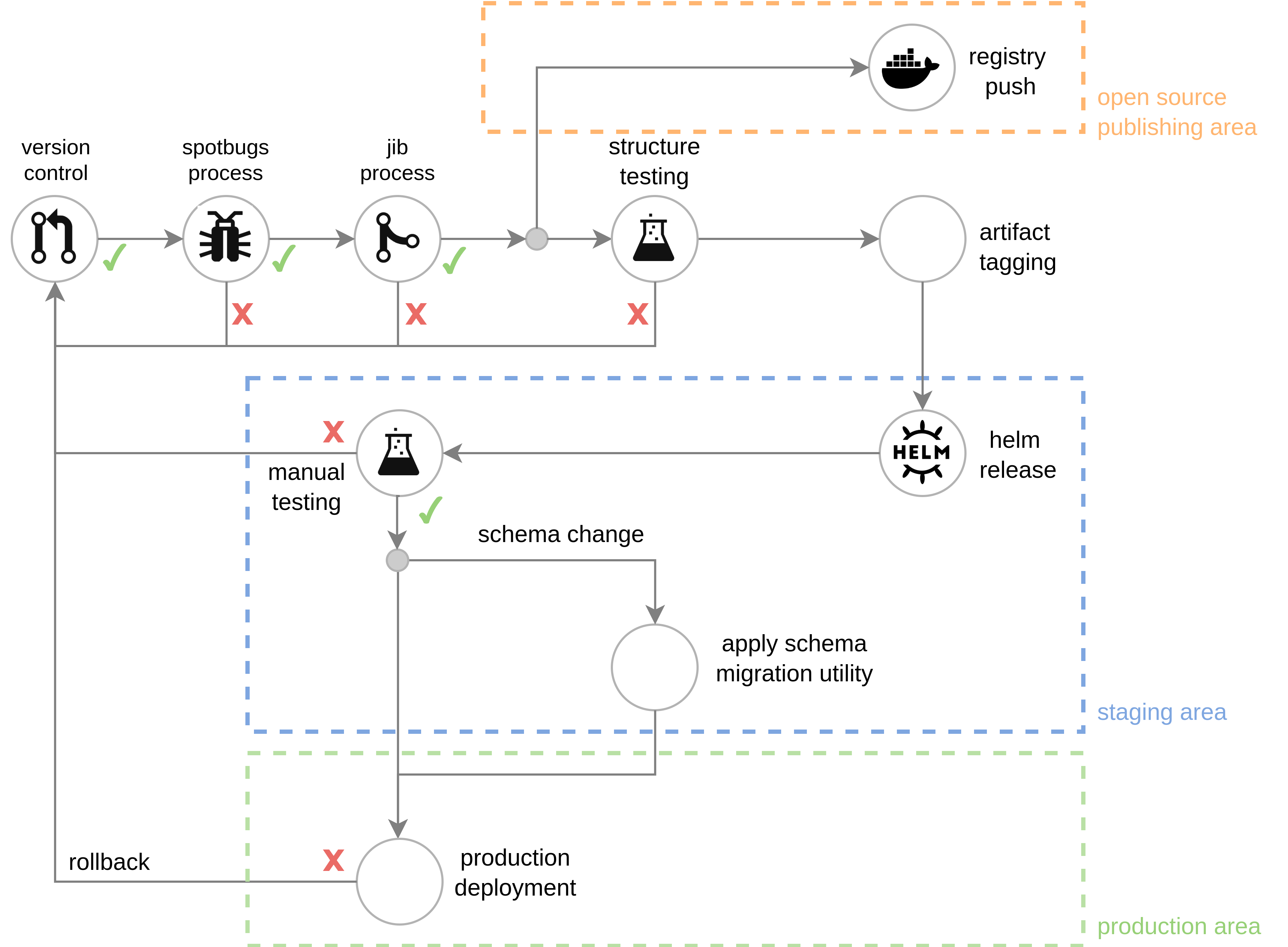

The previous deployment process using Jib would only update the images published to the registry whilst not triggering any changes in any deployment. Combining the Jib build methods with the Skaffold tool will facilitate the continuous delivery of code changes to the k8s deployment itself.

Integrating skaffold into the Travis pipeline would allow a hands free rolling update on all containers whose code is affected by the change. However, despite its integration testing functionality based on container-structure-test, this tool is not mature enough to be applied in a stable production environment and should be delegated to the development environment to provide a direct source code to deployment solution.

Pod hardening

Pod security contexts are particularly tricky to implement but allow for enforcing privilege and access control settings for a Pod or Container.

Enforcing UID and GID

By default, the group and user run in a pod/container will be root(0). Due to security concerns and possible privilege escalations, specifying a different UID and GID constitutes good practice. The nobody user (65534) is the “go to” UID for this task, who in Unix systems has the lowest privileges possible. However, this practice is questionable due to file permission issues as this user is meant for files that must not be accessible by anybody. Keeping a common easy to remember and non conflicting id (over 10000), we can pick 12000 as an UID and GID for all containers.

Granular capabilities attribution

In order to respect the principle of least privilege, a pod should must be able to access only the information and resources that are necessary for its legitimate purpose. Linux capabilities offer a mechanism through which to satisfy this principle by dividing the privileges traditionally associated with superuser into distinct units. For example, granting a pod the CAP_CHOWN allows the process to make arbitrary changes to file UIDs and GIDs. It is impossible to create a set of rules for all container use cases but through trial and error, we have managed to establish a minimal set of capabilities required for a container:

CAP_NET_ADMIN: allows for performing network-related operations (for instance modify routing tables and binding sockets).CAP_DAC_OVERRIDE: allows for bypassing read, write and execution permission checks (useful for containers that require disk operations).

It is important to note that the granularity provided by Linux capabilities is often too large (capabilities are either not sufficient for execution or as permissive as root). AppArmor or SELinux is more adapted for fine-grain pod security context hardening.

Secret administration

Solutions for storing and injecting credentials and sensitive information were then examined in order to properly secure the database access.

Native secret storage

k8s secrets are objects that store a key value map with the value being base64 encoded and not encrypted. Therefore, committing these values to the source control (in our case git) is not recommended. However, in our case, the potential damages can be nullified because the operational git repository is hosted in the private Github Enterprise at the expense of extra effort required to maintain both an open-source repository and a private one.

Credentials can also be obfuscated completely from declarations by using Kustomize’s secret generators or ignoring production values.yaml files if Helm is used. These “hacks” does not address the issue of having plain text credentials in the repository.

Hashicorp Vault

Vault is meant to address the complexities of secret management by centralizing management and access enforcement to secrets and systems based on trusted sources of application and user identity. In the context of k8s, it allows for a pod to use given service account token to dynamically fetch the appropriate secret. These dynamic secrets encrypted both during storage in the Vault database and during transit. Although, the shift to an Identity based access to dynamic encrypted secrets would be perfect from the security point of view. The overhead cost of the Vault deployment cannot be justified in our use case despite the advantages.