Eclipse/steady — Database management

The vulnerability database is at the heart of the tool, storing construct changes, CVE information, vulnerable constructs discovered in scanned applications, etc… This database requires that a couple properties be respected:

- Persistence: data stored in the database should not be deleted by external processes or objects until the user deletes it. It should withstand outages (maintenance operation, schema change, node failure, disk failure, etc…).

- Coherence: any given database transaction must change affected data only in permitted ways and any transaction started in the future necessarily sees the effects of other transactions committed in the past.

- Performance: queries should be resolved at the lowest latency possible for the lowest amount of resources allocated possible. This dual optimization will require an in-depth study of a sample of commonly used queries.

- Schema change and Rollback: the schema of the database is prone to change over different releases. This change is propagated to the database through the rest-backend thanks to the Flyway framework attached to the rest-backend component. The selected management method should allow for rollbacks if this migration were to fail and revert from the corrupted data set to a functional state whilst minimizing downtime.

- Backup and Recovery: production critical data should be periodically backed-up so that any disk outage should be recoverable.

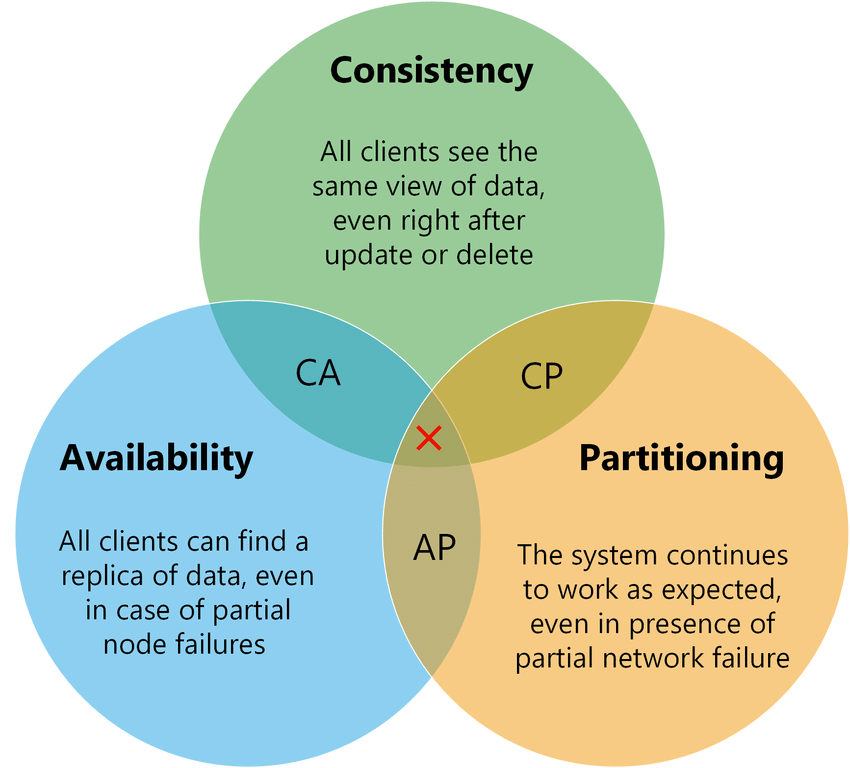

In order to fully benefit from a cloud based deployment, it should also satisfy High Availability (maximize resilience against node failure achievable through data partitioning). However, as per the CAP theorem, these goals cannot be reached as a database cannot simultaneously be Consistent, Available and Partitioned.

Therefore, some trade-offs are to be expected in the final product and one can only maximize two of the previously mentioned attributes at the expense of the third. The CAP theorem is however a point of contention because distributed systems more often than not attempt to maximize each property whilst not fully satisfying any.

Reaching High Availability

Availability and Partitioning through NoSQL:

Achieving these properties can be done through a migration to a NoSQL database. Column oriented database such as Scylla/Cassandra can be an appropriate candidate given a replication factor of 2 or higher. This will require a remodelling of the database scheme by defining the most appropriate partition and sort keys. Some refactoring of the internal application logic is also required to implement data ingestion.

This option would lower the operational cost of managing the database, with the clustering and availability delegated to the DBMS. However, the lack of consistency is not appropriate for the application at hand, as all clients should have the same view of the critical data of a given scan. After considering the available development resources, the refactoring task has also been deemed improbable in the near future. The cost of migration and these problems make a shift to NoSQL infeasible.

Eventual consistency with SQL to reach HA

An SQL database can be clustered in order to reach High Availability in exchange for some loss in strong consistency. A couple of solutions are to be considered:

-

MySQL managed clustering: MySQL offers in-built functionalities for creating a master-slave cluster. Since the current database is already SQL and abstracted through Hibernate, a migration to this model would entail no development cost.

-

However, MySQL is distributed under a convoluted GPL license which stipulates that a closed-source redistribution of MySQL must enter into a commercial license agreement with Sun (the owners of the intellectual property). Since the vulnerability-assessment-tool has two “versions” (an open source one which obfuscates some of the internal one’s source code), this decision would require purchasing a license.

-

Database sharding: Hash based or manual sharding can be implemented software side in order to split the data load into multiple consistent SQL instances. As the development cost of such a model would be exorbitant, this solution is not to be considered despite its benefits to both scalability and performance.

-

PostgreSQL self-managed “clustering”: this uses the master slave replication feature offered in order to create multiple eventually consistent read replicas. This option entail the highest operational cost (for managing the database, backups, etc…) in pursuance of the lowest development cost as well as the most flexibility.

Due to the advantages described above, the k8s deployment will implement a postgres cluster with master slave replication. This method, called Streaming Replication, ensures that a standby server to stay more up-to-date than is possible with file-based log shipping. It streams WAL (Write Ahead Logs, transaction logs that are written to stable storage) records to the standby as they’re generated, without waiting for the WAL file to be filled. Streaming replication being asynchronous by default (there is a small delay between committing a transaction in the primary and the changes becoming visible in the standby), strong consistency is not achieved. However since the delay is negligible, the data is eventually consistent all throughout the cluster.

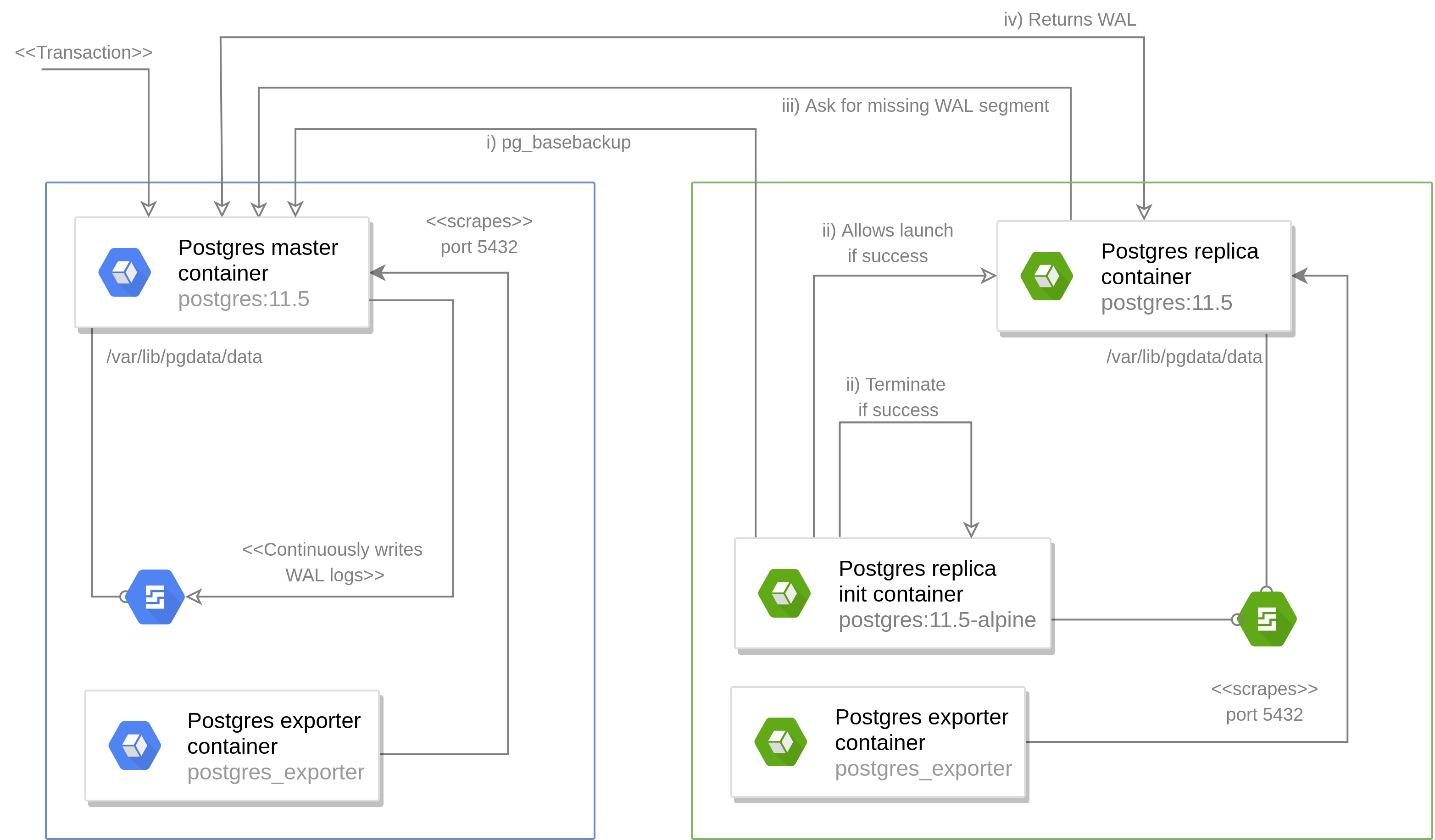

In order to persist volumes on the same node and preserve a meaningful cache, database pods should, once created, stay on the same nodes. A stateful set is therefore the most appropriate controller for this case. As this is a master-slave architecture, the master pods and slave pods are heterogeneous and should therefore be declared in two different stateful sets. In order to set up replication between the master and slaves, the following steps are performed:

- The init container in the postgres replica pod uses pg_basebackup pointed to the postgres master container. This command copies the data from the master node to make sure that the replica is up to date, then generates the replica.conf file which tells the replica node that it is the master’s standby.

- Once the base backup succeeds, the postgres replica container can spin up whilst mounting the same PVC as the init container (thus sharing the data stored in

/var/lib/pgdata/dataas well as the config files)

During this initialization and the course of its entire lifetime, the following interaction between the master and slaves occurs:

- The master continuously writes transactions to the transaction log (WAL). Once the size of the WAL logs reaches a predefined limit, the log is closed and a new one is created. Due to limits on disk storage, these are rotated once a limit is reached and archived.

- The replica nodes frequently queries the master to ask for the most recent WAL segment which it does have and keeps track of the replication lag.

- The master sends the most recent WAL segments to the slave, thus ensuring replication and the transactions are committed to the slaves (Insert/ update queries).

Connection pooling

The replication method used presents one main downside: the read and write streams have to be separate to ensure data consistency, therefore, writing to a replica node is not permitted.

This is where pgpool comes in and acts as a buffer to distinguish read from write requests and proxy them accordingly without having to change the application’s internal logic. This middle-ware also allows for Connection pooling (reducing connection overhead by reusing connections with the same properties), Replication (distinguish between read and write request by analyzing the query), Load balancing (distributing queries between multiple database instances) as well as In Memory Query Cache (increases speed of some requests by storing the SELECT statement result in memory). However, it also comes with overhead costs of its own, querying the database directly would certainly be faster than through any given “proxy”.

Therefore, the ensuing benchmark has been done in order to determine whether or not pooling the database connection is beneficial performance wise.

Benchmarking the database cluster

Reproduction steps:

- Create the database cluster on SAP’s Converged Cloud based on three machines, each mounting a 400GB PVC provisioned by Openstack Cinder:

- 1 * 24560MB RAM, 24 VCPU, 64GB disk hosting the master database

- 2 * 16368MB RAM, 16 VCPU, 64GB disk hosting the replicas

- Use the previous machines as a node pool for running k8s (version 1.15.2) and a 16GiB, 8vCPUs machine from which to run the benchmarking tool.

- Load the production database:

- Total size: 354 GB

- Tuples inserted: 412369404

- Amount of tables: 30

- Run the pgbench tool as a k8s scheduled job within the cluster (on a distinct node from databases) with the following specs (Scaling factor: 1, Query mode: simple, Number of clients: 80, Number of threads: 8, Script: sample of read queries (with varying complexity) representative of the overall population of queries to the real life work load).

Test cases:

- Master direct: pgbench runs directly against the master node with nclients concurrent clients. This would simulate the ‘old’ setup but with replication added on which would slightly tax performance.

- Slave direct: pgbench runs directly against the slave service (with two exact endpoints). This would be the most optimal situation since pgbench clients can query both databases and thus reduce the response time on both. (Purely hypothetical as test cases only touch read-only queries)

- Single pgpool instance: pgbench runs against pgpool connected to one master node and to slaves.

- Multiple pgpool instances (2,3,4): pgbench runs against pgpool-service connected to 3 pgpool non clustered instances.

| tps with handshake difference from optimal setup (tps) | tps with handshake difference from optimal setup (ratio over slave direct) | tps w/o handshake difference from optimal setup (tps) | tps w/o handshake difference from optimal setup (ratio over slave direct) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slave Direct | +0.00 | 0% | +0.00 | 0% |

| Master Direct | - 1.279175 | - 10.6% | - 1.279145 | - 10.6% |

| PgPool | - 2.478072 | - 20.6% | - 2.45631 | - 20.4% |

| PgPool cluster (3) | + 1.251716 | + 10.4% | + 1.2518890 | + 10.42% |

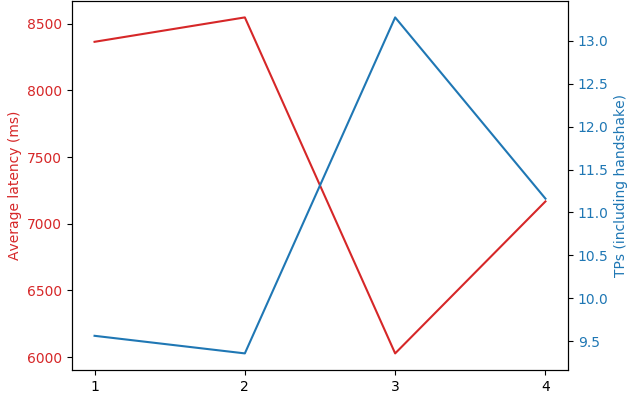

The previous reproduction steps yield the truncated results seen in the above table. Clustering pgpool increases postgres’s performance drastically when it comes to more complex transactions. This is possibly due to the inbuilt load balancing provided by both service layers (pgpool-service) as well as pgpool load balancing mechanism. This comes at a lower performance for simple requests as the constant shifting and handshakes required makes simple queries unviable (sometimes with 300% average latencies than other methods).

Similarly, from the pgpool test case, using the amount of replicas as the variable yields results presented in the Figure below. This confirms that having the amount of pgpool replicas being equal to the sum of the amount of master and slave replicas is the optimal setup to reduce both latency and increase tps. Going overboard with the amount of replicas is also visibly detrimental to the overall system’s health.

Persistence and Resilience

Data stored in the database are critical and should be stable and resilient to outages.

With the replication scheme previously described, even if a node containing a database were to go down, the data persists in multiple replicas and can be easily restored. If the master node goes down, the system is temporarily read-only and the replicas take charge as the sole read endpoints. Therefore data resilience to node outage is partially guaranteed.

On the other hand, network outages can be mitigated using WAL archival in the master node. These incremental backups are vital to allow disconnected nodes to catch up to the replication lag. However, due to the storage limitations and WAL files keep getting generated, the space is bound to be recycled and a replica can no longer use that checkpoint to catch up. The maximum size of WAL logs is therefore of utmost importance and defined by two constant (unable to be changed live) parameters:

$$WALsize = maxWALsize \times WALkeepsegments$$

The deployment can therefore handle all network outages during which the amount of transaction logs written do not surpass $WALsize$. If this time frame is exceeded, manual intervention is required to delete the PVC, PV and Pod and force the recreation of a new replica.

In order to further decrease downtime when confronted to this scenario, Openstack’s snapshot functionality can be leveraged to periodically store a copy of the volume mounted on the master node. This is useful in two scenarios:

- when the master node is corrupted in order to quickly spin up the system

- when replicas have fallen too far behind, the latest snapshot can be mounted to a temporary pod to be demoted (cleaning up the master configuration and mounting the slave one) and then to a newly spun up slave pod. This requires that the snapshot interval must be strictly lower than the period to accumulated an archive of $WALsize$.

Release and database change

Over the development cycle of the vulnerability-assessment-tool, the underlying data model is bound to change and this shift has to be seamlessly applied to the PostgreSQL database. All modules of applications destined to communicate with the database uses a object-relational mapping named Hibernate which translates an object oriented data structure into a set of tables and rows (traditional SQL). Along with Flyway, used for creating and applying incremental schema migration scripts, this creates a continuous delivery pipeline reflecting changes in the application data model in the database.

In edge cases, this migration can fail and corrupt all production critical data so a method to revert the damage is mandatory to maintain this system.

Proposition

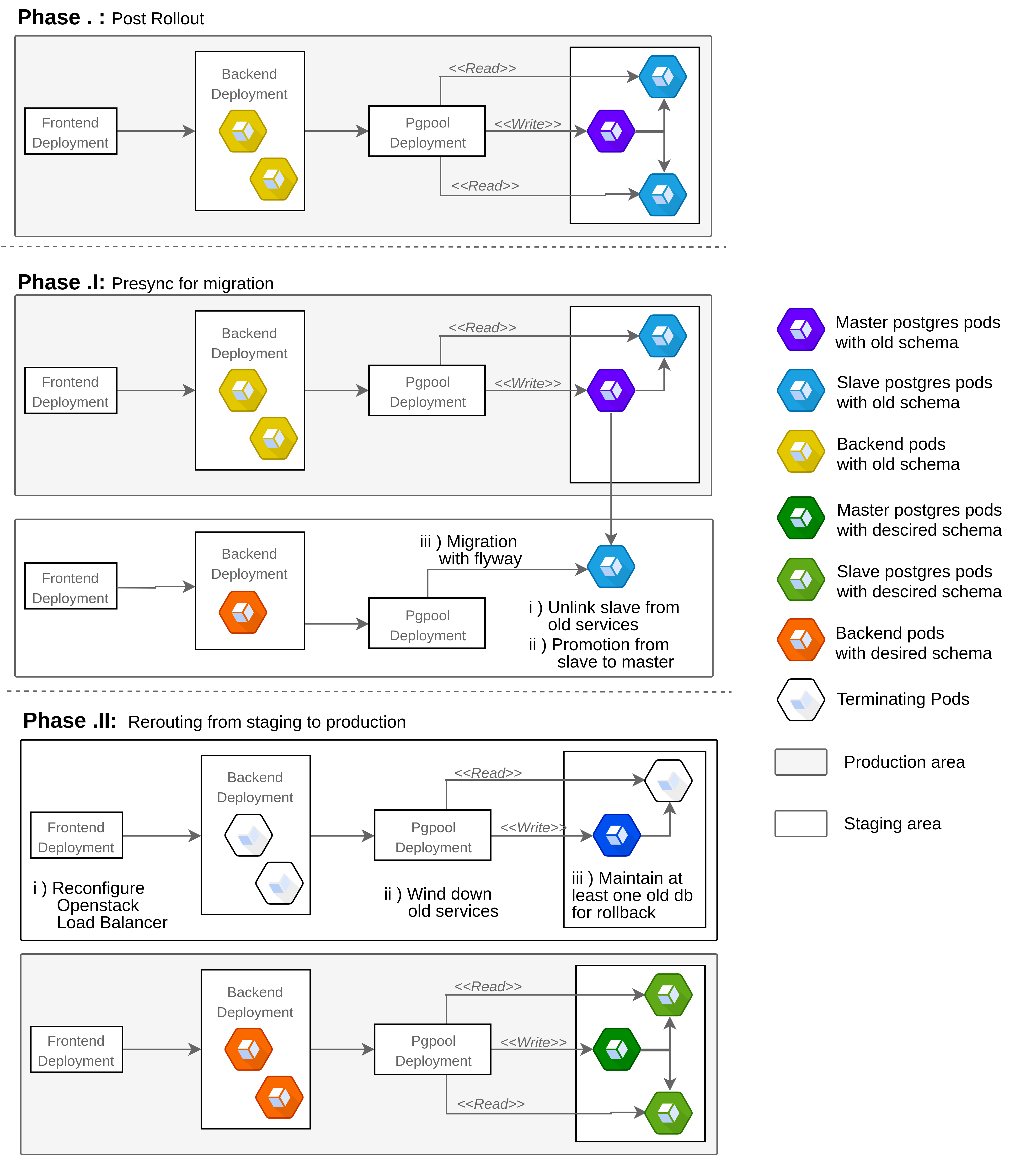

The k8s proposition attempts to address the rollback issue whilst minimising the downtime and maintaining a viable staging environment. An utility, implemented in Golang, has been developed to perform the following actions:

- Fetch the amount of replicas of the postgres slave stateful set in the given namespace and cluster (at least 2 replicas are required to have a no downtime upgrade).

- Scale down one replica from the slave statefulset and store the name of PVC mounted by this replica (which will persist after the scale down operation). This effectively makes an instant k8s native snapshot of the master database whilst keeping the old deployment completely functional.

- Create an ephemeral job that mounts the previous orphaned PVC and promotes the slave to master (by deleting the recovey.conf file).

- Spin up a new release (core chart) with a new release name with the master mounting the previously promoted volume. The new rest-backend (Flyway has its own data race management mechanism which only permit a single instance to perform the migration) then applies the schema changes without threatening data loss (the old release still coexisting).

- Once the administrator validates the changes in the staging release, reroute the load-balancer/ingress controller to serve the staging release and remove the old one, effectively promoting the staging area to the production one.

In order for two environments (staging and production) to coexist without conflicts, every service selector has to be specific to the release and the labelling scheme must be strictly implemented (with all object having the appropriate release name as a label).

This method guarantees a near 0 down time upgrade with the only time-consuming step being the populating of the newly spun up slave replicas which takes around 5-6 minutes for a data load of around 350GB. During this step, the old release will still be completely functional but any write operations won’t be translated to the new deployment. When it comes to the rerouting, it could be done via LoadBalancer rerouting (which directly depends on the cloud provider implementation) or by modifying ingresses selectors and live ingress controller reloading for an instant reload.